This piece was written by Marisa Rando.

As we strive for progress, we often overlook the lessons that the past holds for us. Like kids, we feel that earlier generations don’t understand us - as if all our problems are unique and require newfound innovation. We see life as temporal and novel when in reality, we live in a series of cycles - the same happenings repeating themselves over and over again.

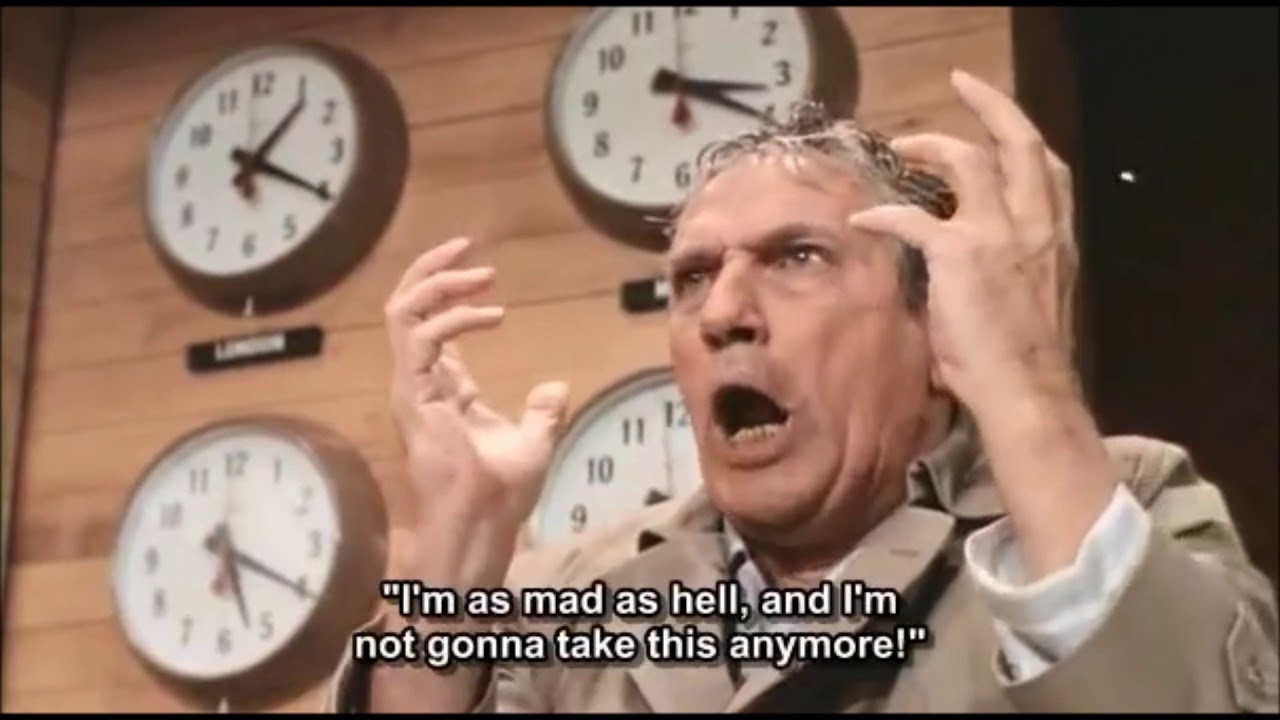

I was reminded of this the other day when I rewatched one of my favorite films called Network. Released in 1976, it tells the story of a news anchor about to be let go after years on the job because of low ratings. This triggers psychological distress that causes him to lash out on air about the harsh realities of the world - inflation, recession, crime, conflicts with Russia (sound familiar?). Without giving too many spoilers (because I really want you to watch it), the film follows our protagonist to the underbelly of the media machine - showing his rise to stardom when the network profits off of his “refreshing perspectives” until things start to turn. Our world now faces an eerily similar avalanche of issues, paired with high media skepticism. Unsurprisingly, today only 7% of Americans indicate a high level of trust in news media.

Network called out nearly 50 years ago what has become common knowledge today. Traditional news media is no longer an engine for truth-telling. Their form of “journalism” prioritizes shareholders over people - using sound bites, sensationalist headlines, and narratives that serve political and corporate interests to keep people hooked and ratings high. It is no wonder we refer to “the media” in such a derogatory way as the harm it causes us is palpable.

Some see the emergence of social media as a major step in progress against this centralized control because of how it's enabled anyone to share information from anywhere, at any time. However, any person with an Instagram or Tik Tok knows that it’s far from a liberating experience. The consistent selling and stealing of our attention/personal information is certainly not a negligible point - but in the context of decentralized “free speech”, what’s most concerning about these platforms is the content they censor. With these centralized forces as our standards for media, it feels easy to forget that media has also served as a tool to create revolutionary change.

Revolutionary media

The revolution will not go better with Coke

The revolution will not fight germs that may cause bad breath

The revolution WILL put you in the driver's seat

The revolution will not be televised, will not be televised

Will not be televised, will not be televised

The revolution will be no re-run, brothers

The revolution will be live

-Gil Scott-Heron

Released a few years prior to Network in 1971, these words were born out of a similar frustration with the corruption in news media. In the real world, was a country deep in upheaval over the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War - on television was commercial media selling the idea of a “perfect America.”. The Revolution Will Not Be Televised is a powerful rallying cry not only for Black liberation but for a nation to turn its backs on the false sense of security promised of corporations and take action.

Though the message has been misunderstood to mean “there will be no live media coverage of the revolution,” — this is not what Scott-Heron is saying. The poet is suggesting that the revolution can not and will not come at the hands of profit-motivated corporations and that revolution is not a passive activity. One cannot simply consume it, retweet it, or make an aesthetic of it. The revolution (both as something personal and societal) is an active commitment to dismantling systems of oppression.

This cautionary tale resonates today as we’ve seen media used as a form of performative allyship from companies to drive more sales or as a tool to make activism as easy as sharing an infographic to your Instagram. Scott-Heron’s words urges us to think more critically about what we consume, how we create, and what real-world action we’re taking.

Media created by grassroots organizing groups has emerged as a counterforce, with the designed intention of promoting solidarity and a sense of belonging. These groups utilize collective media creation - a democratic and decentralized process that prioritizes the perspectives and values of all participants involved. For these groups, this process is a forcing function to practice their values and is also a liberating act itself.

This is what collective media looks like

If we want to create media that’s truly collaborative and decentralized it’s essential to examine the success of grassroots organizing, as their approaches are grounded in an understanding and unlearning of the systems that push us into hierarchy and isolation, to begin with.

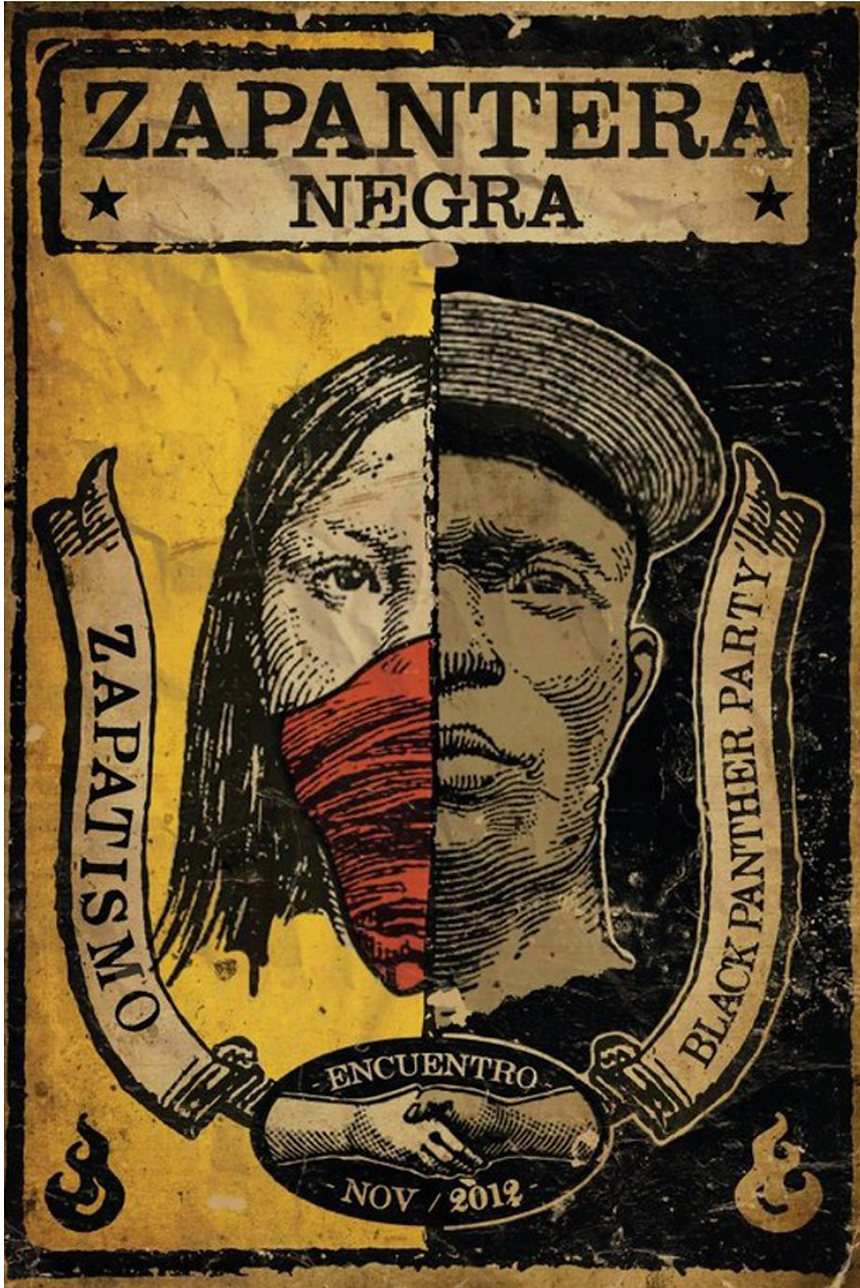

Groups like the Black Panthers in the United States, the Zapatistas in Mexico, and the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) all over the globe have been leaders in this work. To them, making media wasn't about selling ideas or “building a brand” for their organization. It was a vehicle for demonstrating their values, building a strong collective, amplifying underrepresented voices, and prefiguring the better world they believed was possible. Below are a few of the principles grassroots organizations have used to tell collective stories and mobilize millions.

Decentralize creation

Growing up in a perpetual workforce, determining our value by our productivity, it is extremely hard to slow down and let go of control. In my early days of organizing, I thought I could come in and shake things up. I’ll show them what I’m capable of. Ultimately, I realized that performance and standing out is not what this work is about. It’s about re-imagining these structures of individualism and output we’ve been given, not just applying them in different settings. Most of us find it challenging to break free from broken frameworks and dream up something better collectively. But not the Zapatistas.

The Zapatistas, a notable Indigenous organizing group in Mexico, have a core belief about the way they operate — their goal is to create ‘Un Mundo Donde Quepan Muchos Mundos’ (‘A World Where Many Worlds Fit’). A world where difference and nuance are things to be honored, respected, and nurtured. This differs even from the world of radical organizing itself as many groups throughout history have treated their practices like a religion with rigid texts to recite and centralized leaders to follow.

Their principled yet flexible approach has led to an impressive flourishing of feminist leadership and education and the creation of multiple autonomous rebel Zapatista municipalities. While each community maintains its values/practices of Indigenous traditions, horizontal governance, gender equity, mutual aid, and agro-ecological food sovereignty — they’ve designed localized democracies to give them both sovereignty and support from the core organization.

The Zapatistas refuse to rigidly define their way of living (what the outside world calls Zapatismo) because they see their struggle as one small part of a collective fight against capitalist exploitation. Their success in building a resilient and radical base has come from building solidarity not only with other Indigenous Mexican communities but with liberation movements around the world.

Prioritize intersectionality

"Whenever you conceptualize social justice struggles, you will always defeat your own purposes if you cannot imagine the people around whom you are struggling as equal partners."

- Angela Davis

Angela Davis was a core member of the Black Panther Party and a fierce advocate for intersectionality - a practice that looks at the connectedness between all types of identity markers (race, class, gender, etc.) and how they relate to systems of oppression - in the Black Liberation Movement. Between her speeches, interviews, and book ‘Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement,’ she has been a consistent voice for solidarity across many global crises as examples of the same capitalistic, colonial, racist injustice. To Davis and many others in the Party, the analogizing of these struggles not only helped grow their supporter base but kept their party focused on the end goal - dismantling all systemic oppression.

Building bridges of solidarity is crucial to effectively organize and create motivating, expansive media. Whether it be illuminating the voices of Palestinians living under apartheid to combat the narrative of a fair “conflict,” or giving voice to the victims of police brutality in the US - The Black Panthers were consistent in their showcasing of stories across Black and brown communities all over the world. Lifting up their voices and advocating for their shared struggles strengthened all of their movements simultaneously.

The Party for Socialism & Liberation (the PSL) is a present-day global organizing group that takes an intersectional approach to their work. Their online publication, Liberation School, covers political happenings in Cuba, China, the United States - and everywhere in between. Wherever there are people organizing, it is very likely the PSL is involved and/or reporting on it. Also, based on Marxist-Lenninist ideology, they keep their focus on combating capitalism anywhere and everywhere it perpetuates inequality, rather than targeting specific groups or pundits.

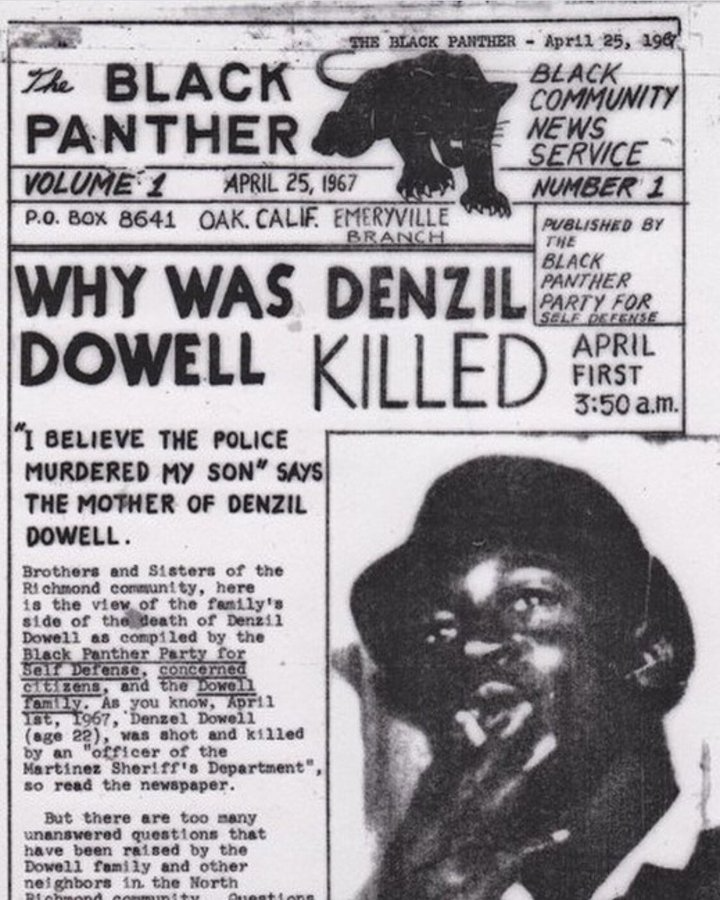

Serve the people

In April of 1967, long before Twitter and smartphones, the family of a young man was desperate to get more information on the death of their son. They were rejected by law enforcement and the local news media, who dismissed their concerns. The family decided to reach out to members of the Black Panther Party for help getting clarifying information, support, and justice for their son. The murder of 22-year-old Denzil Dowell by a sheriff’s officer in Richmond, California, was the catalyst for publishing the first Black Panther, the newspaper of the Black Panther Party.

Their first issue — while novice in design with handwritten elements, misalignment of layout and photos, clearly photocopied — served a meaningful use. It let the public know that the police were omitting facts of Dowell’s death without accountability, asked for their help in demanding justice, and encouraged them to organize for self-defense.

The Black Panther became a powerful tool for the Party that would continue all the way until 1978, inspiring so many staples of the modern Black liberation movement — like the image of the clenched black fist to the slogan “All Power to the People”. Unlike many of the publications of today, its intention was not to entertain, boost subscribers, or drive ad sales. The newspaper was created to serve a real need — to be a vehicle of communication and organizing for the people.

Much of how we see grassroots organizations using social media today mirrors this principle. Requests for resources for a neighbor in need, rallying support for a protest, amplifying stories of injustice - groups today know that media is a tool and put it to good work. So if you want your media to captivate people, ask not how your media can entertain, but how it can practically serve its readers.

Keep it real

Organizing is messy work. But so is living. And in both instances, we pretend this isn't the case. We obsess over the perfect wording, lighting, and aesthetic — wanting to give the illusion that everything is neat and orderly. When it comes to our organizations and their “manifestos'', the same is true. What we see today are often poetic, intellectual narratives coming from one central voice for “brand consistency”.

While it makes for nice reading, there’s real harm being done when we work to apply polish over our outrage and humanity. Our desire to hide the messiness of decentralized work in an attempt to appear more intelligent or “put together” and appease a more high-brow audience rejects the values of the collective itself. David B. Holt advises against this strategy in his essay "Why the Sustainable Economy Movement Hasn't Scaled". He claims when we try to make our impact-driven efforts more “marketable” to an influential mass (who he refers to as “bourgeois bohemians”), we further isolate the ‘average worker’ we claim to be trying to serve (who he calls “Main Street”). In other words, we cannot “glamify” or intellectualize our efforts — we must normalize and embrace our messy humanity.

In my work with Pact Collective, an organization focused on mutual aid, collective healing, and political education in New York City, we’ve had similar conversations. Should we talk about mutual aid as something hip and happening to drive more donations? How does one market mutual aid anyway? While these statements are clearly exaggerated, the testament remains that we should be careful not to let corporate thinking and strategies seep into the world of social justice. In Pact's experience, prioritizing connection with our neighbors through real-life events over digital campaigns for potential donors has always yielded the most effective (and enriching) results.

The raw, authentic manifestos like the Zapatistas and the Black Panther Party, which read like recorded speech, are examples of authentic and inclusive content done right. They’re simple, clear, and accessible — which likely explains why they were able to garner such large-scale support. Inspired by this work, a local mutual aid group that I organize with recently decided to rewrite our collective mission statement together. The end result is a mix of everyone’s perspectives (gathered via Google Forms) meshed into a beautiful creed that has all of our words.

Whether it be technology or media, this principle of co-creating something that genuinely reflects the whole rather than creating to impress is where we must change if we want people to see themselves in our missions. As a person who’s spent many years copywriting, the motto I and many peers have followed to simplify technical or academic language has always been to write it how you’d speak it. If your work is genuinely meaningful, you’re likely to inspire people by simply telling it like it is.

Take action

Words can inspire, but only action can make us believe. Despite the revolutionary ways in which these groups have created media, these organizations wouldn’t have become household names without direct action. The Black Panther Party hosted countless community aid programs that helped feed and clothe their neighbors, provided culturally-relevant education, and even gave free transportation to prisons so people with incarcerated loved ones could visit them. The Zapatistas did the intense work of assembling armies, fighting for their freedom, sacrificing their lives, then later building self-sustaining communities based on care and mutual aid. Members of the PSL all over the globe continue to show up for their communities by protesting in the streets, helping tenants and workers unionize, and providing accessible education on liberation.

This is probably what Scott-Heron meant most fervently in The Revolution Will Not Be Televised — that writing tweets and “making content” cannot be an act of revolution unless it is paired with meaningful action. For these groups, their media serves as artifacts of their real-life work and influence — not as a projection of their ideas and dreams.

Many organizations I’ve been a part of have fallen into this trap too. We think that content is powerful enough to affect change. We start our impact-driven organizations the way we would start a business - by creating a website, being vocal on social media, raising funds, and printing zines. What we fail to realize is that these are all accessories of a movement, not their driving force.

When we create as a collective, we have the opportunity to build community, increase accessibility, empower each other, and resist censorship and centralization. As a recovering marketer, I am haunted by terms like “content is king” — because in the real, material world, people are too smart (and skeptical) to be sold on promises printed on flyers in trendy fonts. It’s consistency, inclusion, and real value that get people’s attention. If you want to start a movement, forget about saying the right thing — just roll up your sleeves and get to work.